Bridging the Gap: Appropriate Farming Technology for Scaling Agroecology in West Africa

A new pilot challenges high-tech farming narratives, showing how appropriate tools for agroecology can deliver real gains for West African farmers.

In West Africa, around 80% of the population relies on agriculture, with smallholder farmers producing most of the food consumed locally. Many are turning to agroecology to improve resilience and food security, but the heavy labor demands of agroecological farming limit its adoption. One critical solution lies in what development practitioners call “appropriate technology”—not expensive electronics or AI, but simple, affordable tools designed for local conditions that farmers can use, maintain, and repair themselves.

Farming in the region is still overwhelmingly manual. Across Sub-Saharan Africa, an estimated 65% of agricultural work is done by hand and another 25% by animal power. Women carry most of this burden, often walking long distances, weeding by hand, and processing harvests manually, while having the least access to tools designed around their needs.

Mechanization could ease this burden, but market forces and policies rarely incentivize the development of appropriate, affordable tools for soil management, planting, harvesting, processing, and marketing. Instead, private investment and development funding flow towards grand-scale, high-tech solutions like drones, artificial intelligence, and precision agriculture, framed as the future of farming. Investment in AI in agriculture alone is projected to grow from US$1.7 bn in 2023 to US$4.7 bn by 2028. Meanwhile, simple tools like a roller seeder that cuts a week of planting to a single morning remain underfunded and hard to find—part of a broader $117 billion financing gap facing smallholder farmers and agricultural SMEs across sub-Saharan Africa.

There is a clear need for appropriate technologies to support farmers in their transition to agroecology. It is this gap that prompted Groundswell International and its partners to launch a pilot program in Mali and Ghana between January and September 2025, working with Sahel Eco, Urbanet and CEAL, with support from the 11th Hour Project.

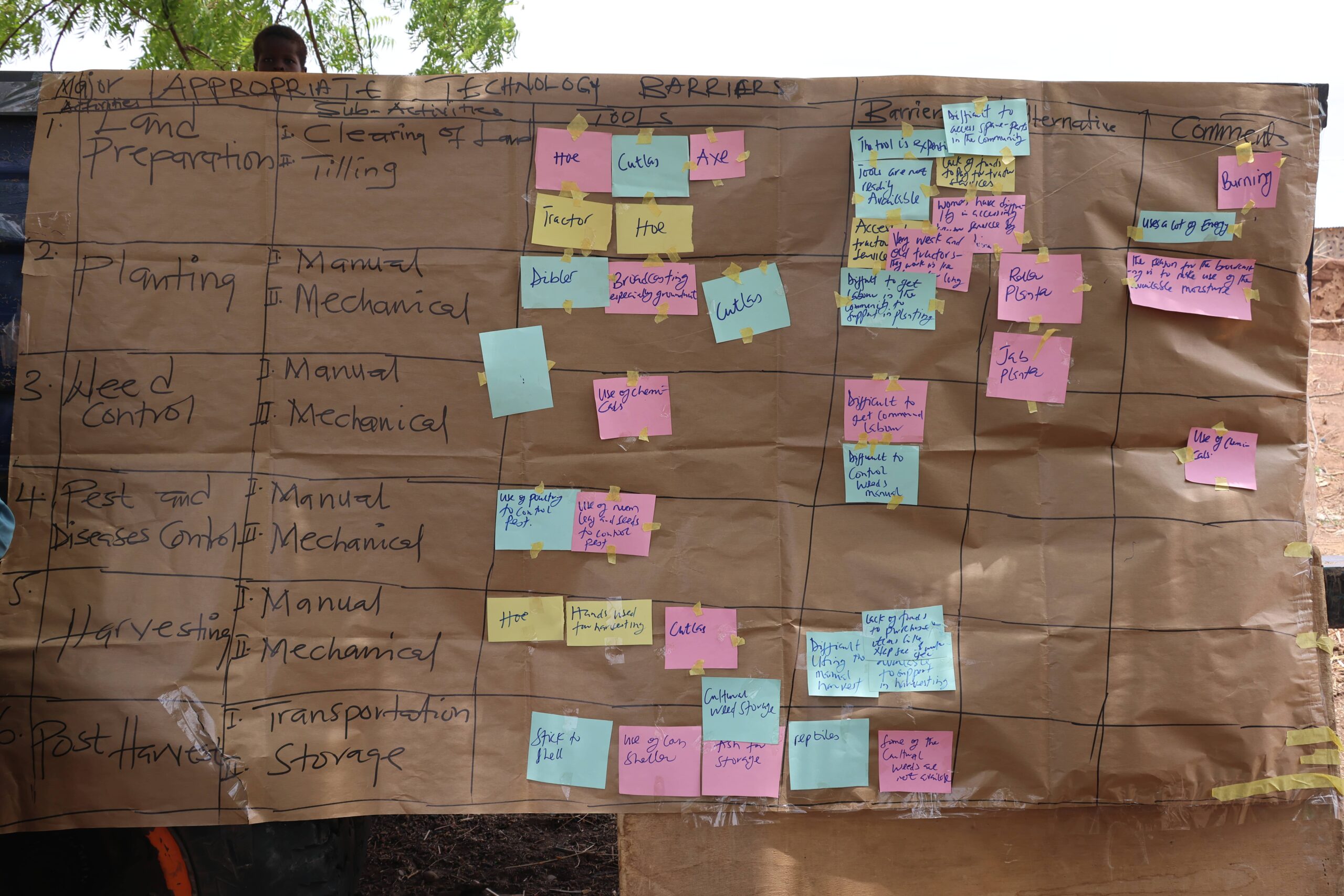

Rather than importing solutions, the project adopted a farmer-led, participatory approach to identify priority tool needs that fit agroecological systems and smallholder farmers’ realities, test and adapt tools in local contexts, enable small-scale manufacturing, repair, and distribution networks, and document lessons to inform scaling across West Africa.

The result is practical, ground-level evidence that appropriate farming technology, neither futuristic nor expensive, can reduce drudgery, raise productivity, strengthen and favor the expansion of agroecological systems, and build local economies.

What is Appropriate Technology?

Appropriate technology refers to tools and practices designed to match local needs, skills, and environments, rather than impose external models. In agriculture, this often means equipment that is:

- Simple: easy to use, fix, and understand

- Affordable: low investment, low upkeep

- Locally adaptable: built or repaired with materials and knowledge close at hand

- Ecologically aligned: light on the soil and gentle on ecosystems

Appropriate farming technologies offer immense potential to improve productivity while easing labor and limiting soil degradation, especially in the context of the agroecological transition.

Co-designing appropriate farming technology for agroecology: Innovation by and for the people

The Appropriate Technology project’s methodology centered on a learning-by-doing process that began with a single question: What tools do farmers themselves consider appropriate? It then followed 4 distinct phases.

1. Participatory research with farmers

In Ghana and Mali, groups of farmers with at least 50% of women met in workshops and field discussions to identify the tasks that drained their time and energy, from seeding and weeding to post-harvest processing. Women farmers consistently highlighted how limited access to basic tools delayed their work and reduced productivity.

2. Local scan of tools and enterprises

Partners then mapped the existing landscape of tools (their availability, costs, and maintenance needs) and explored opportunities to strengthen local manufacturing and repair services. This included identifying ways for women and youth to participate in small-scale enterprises that produce or service these tools.

3. Co-designing and testing tools

Farmers collaborated directly with local artisans and small manufacturers to adapt or develop equipment suited to agroecological practices. In Ghana, CEAL hosted workshops in six villages where farmers and artisans jointly redesigned simple tools. They tested roller planters, solar sprayers, and organic fertilizer applicators in demonstration fields. By the end, 159 farmers had access to improved tools that reduced drudgery and enhanced productivity.

In Mali, Sahel Eco applied a similar approach with farmer cooperatives and artisans. Local workshops led to the development of improved versions of everyday tools, including hoes, machetes, ploughs, wheelbarrows, and manual roasters, and inspired new designs, such as honey filters and hoeing machines. These collaborations demonstrated how local knowledge and craftsmanship can transform simple ideas into practical innovations that align with agroecological systems.

4. Building local networks

The process also strengthened ties between farmers, tool producers, and repair services. Some artisans expanded their workshops, while communities explored tool-sharing models and local markets to acquire better equipment, laying the foundation for self-sustaining innovation networks.

Appropriate farming technologies examples: what worked and key learnings

1. Tools improving productivity

Farmers reported major time and labor savings with roller planters, fertilizer applicators, and solar sprayers. Some tasks that used to take a week can now be done in a day. Appropriate technologies, identified through previous consultation with farmers and network members, can be organized into three categories, with examples listed below:

| Category | Examples of Tools / Technologies | Notes / Opportunities |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Soil Preparation and Health | – Low-till and no-till tools, including seeders – Seed pelletizing machines (e.g., bicycle-powered pelletizer) – Hoes for cutting weed tops while leaving roots in the soil – Tools for improved compost production – Simple soil-health testing tools – Presses or devices that increase efficiency of producing bio-inputs (pesticides, fertilizers, etc.) – Cutlasses for tree pruning (e.g., FMNR systems) | – Bio-input production is often slow and labor-intensive; improving efficiency could boost farmer uptake. – Increasing awareness and production of bio-fertilizers is important, especially as the African Union’s 10-year African Fertilizer and Soil Health Action Plan (2024) promotes heavy use of synthetic fertilizers. |

| 2. Post-harvest Storage, Processing & Transport | – Processing tools (milling, drying, etc.) for added value of crops and non-timber forest products – Grain storage silos and seed-bank structures – Transport tools: bicycles, motor/tricycles, animal-drawn carts | Improved processing and transport reduce losses, increase income, and support local markets. |

| 3. Water Management & Irrigation | – Rainwater harvesting systems: ponds, cisterns, sand dams – Water-access tools for dry periods: wells, boreholes, solar pumps, motor pumps – Irrigation solutions: drip irrigation; gravity-fed, solar, or electric irrigation tools | – Efficient water movement from wells/boreholes to gardens is a priority. – Some Malian communities already use solar-powered borehole pumps; others seek low-energy irrigation options. |

2. Women’s access to tools

The project also focused on improving women’s access to tools, who often rely on their husband’s equipment. Better access to tools meant women could plant on time, increasing yields and autonomy. As Zilatah, a farmer from Torope supported by Urbanet, explained:

“The hoe you keep calling simple is not simple for me because I don’t even have one. If I had my own, I could work faster every season.”

Before the project, Zilatah relied on her husband’s worn hoe and often had to wait until he was finished to begin her work — a delay shared by many women farmers. These accounts highlight how equitable access to appropriate technologies directly supports gender equity and women’s economic independence.

3. Seed and cost savings

Improved seeders reduced seed use by 40–60%, freeing up resources for other household needs.

4. Community organization and learning

Farmer-to-farmer training spread rapidly through agroecology committees, which helped share tools, coordinate planting schedules, and engage local leaders in supporting these innovations.

Challenges and Lessons

The pilot revealed a clear appetite for appropriate technologies, but also the need for continued support. Droughts delayed testing in some areas, and not every village had enough tools to share. Some farmers needed ongoing coaching to master new equipment, and this requires stable staff, resources, and long-term funding.

What’s Next

The project will expand to 15 more communities across Mali and Ghana, strengthening local tool-making and repair enterprises, especially those led by women and youth. The next phase will also test more appropriate technologies for water management and processing to reduce labor further and improve food security.

As we continue to document these results with our partners, these lessons are helping shape policy discussions across West Africa on how to make mechanization inclusive and climate-smart, prioritizing local innovation over imported machines.

Ultimately, this work shows that the real test of innovation is not how advanced a technology is, but whether it improves the lives of those who depend on it. By that measure, appropriate technologies for smallholder farmers are not secondary to “big” innovations; they’re what make sustainable change possible.

Go further: Read Agroecology Pays Off in Burkina Faso: New Study Shows 77% Yield Gains and Strong Financial Returns Despite Extremely Dry Conditions