Restoring Ancient Ahar-Pyne Water Systems: A Rebirth of Traditional Farming Practices in India

Co-authored by Barsha Koirala and Maylis Moubarak

In the flat farmlands of Surungabigha in Southern Bihar, a dry body of water had been quietly fading into memory. The ahar-pyne — a traditional irrigation system developed by smallholder farmers — had long been abandoned. The land around it was barren, weeds growing in clumps where water once flowed. For local farmers, it was a visible reminder of colonial times, when British-imposed “modern” irrigation methods and land policies pushed aside community-built systems and the knowledge that once kept these lands fertile.

But over the past year, the ahar in Surungabigha has begun to change. What was once dry soil now supports over 450 trees, a green corridor along its edges, and growing community engagement where children and adults work in solidarity.

The Ahar-Pyne system: Bihar’s ancient water lifeline

For over 2,000 years, the Ahar-Pyne irrigation system shaped farming and daily life in South Bihar. Developed during the Magadha dynasty, it is a community-managed water network designed to store, distribute, and conserve water during both the monsoon and dry seasons.

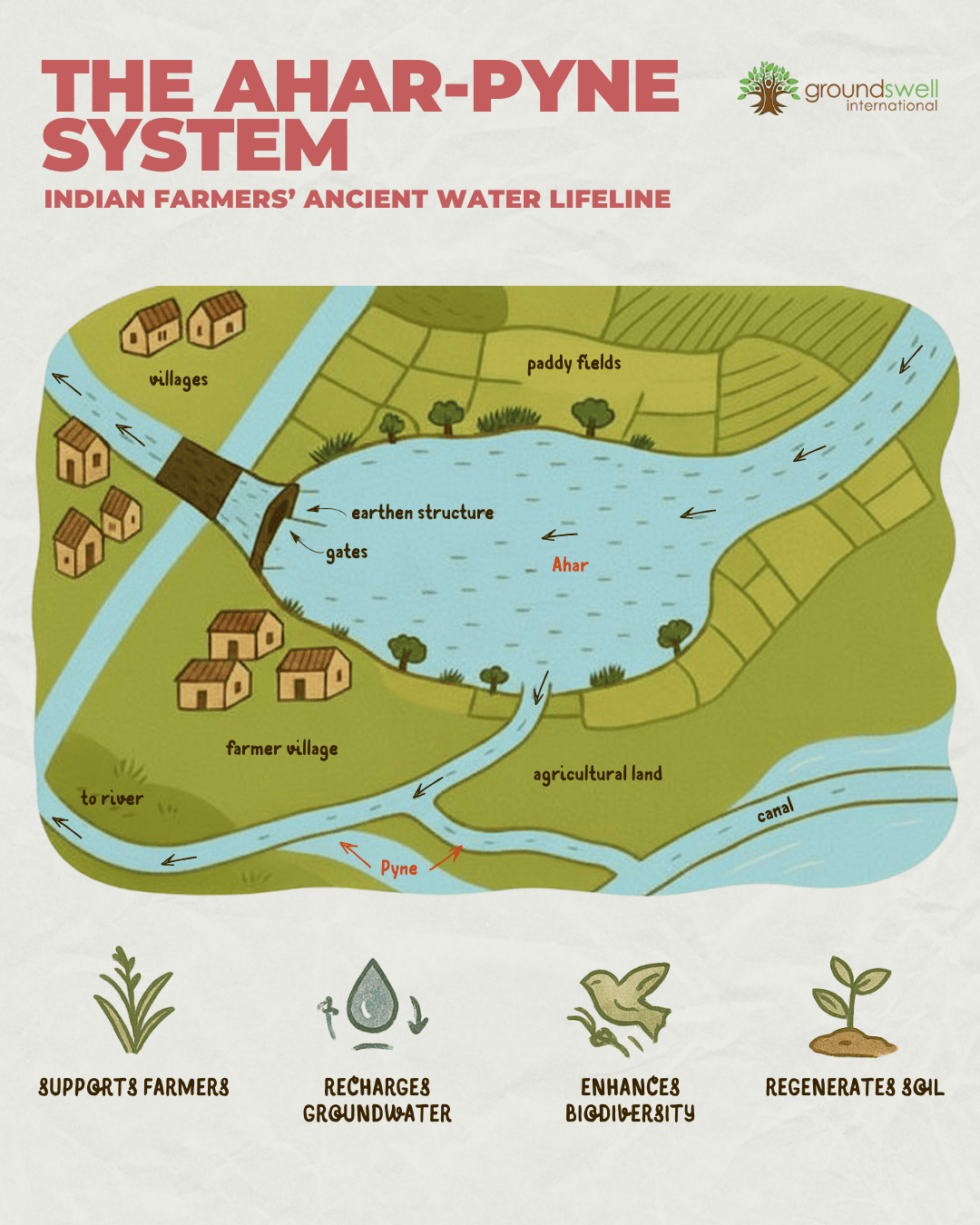

The Ahar-Pyne network has two main components:

- Ahars: Reservoirs with embankments on three sides, built to store harvested rainwater or diverted river water.

- Pynes: Local name for diversion channels that carry water from rivers or streams into and between the ahars and surrounding fields, forming an interconnected water storage and distribution system.

It’s a simple yet ingenious design that allows communities to make the most of every drop of water, especially in South Bihar, where poor water retention and alternating floods and droughts make farming a constant challenge.

A circular low-tech, high-impact irrigation system

The Ahar-Pyne system sustains both farmers and ecosystems in South Bihar. By capturing rainfall and river runoff along steep slopes, storing it in reservoirs, and circulating it through channels, the system ensures steady irrigation even in water-scarce areas. Unused water eventually flows back into rivers, completing a natural cycle that replenishes groundwater, conserves water, and supports local hydrology.

Key Benefits:

- Improves soil fertility by creating nutrient-rich pools that improve crop yields. According to farmers from the Patesar village, irrigation through the Ahar-Pyne system produces 1.5 to 2 times higher yields than other sources like canals or groundwater, as reported by the Millennium Water Story.

- Reduces flood damage by channeling excess rainfall into reservoirs instead of letting it wash away.

- Supports biodiversity by maintaining micro-ecosystems around reservoirs and channels.

- Multi-use reservoirs: Areas remain submerged only 4–5 months a year; farmers use them for cropping and grazing the rest of the time.

Ahars are also low-cost, resilient, and easy for rural communities to adopt:

- Ahar-pynes are built with local materials and are easy to maintain.

- They are economically beneficial for farmers since they lead to higher yields and income.

- They help build climate resilience. By improving soil moisture and enhancing water availability, it helps manage floods and droughts.

- They foster community solidarity: Because different communities depend on the same water resources, people work together to maintain embankments, manage distribution, and share benefits equitably.

Unlike many modern irrigation methods, the Ahar-Pyne is not exploitative—it works with natural cycles, balancing agricultural needs with ecosystem health while strengthening community ties. For generations, the system has supported farming livelihoods but also built social cohesion. In many villages, water brought people together, promoting cooperation, shared responsibility, and collective decision-making.

Illustration adapted from “Ahar Pyne – Traditional Water Harvesting System of Bihar.” BPSC Notes, 16 May 2019

Why the Ahar-Pyne irrigation system fell into neglect

The Ahar-Pyne system began to decline during the British colonial period (1858-1947). The introduction of modern irrigation technologies like tube wells, deep borewells, and canal systems, shifted attention away from these traditional practices. Over time, this led to:

- Depletion of groundwater as reliance on borewells increased.

- Abandonment of traditional reservoirs. Many ahars became clogged with mud, overgrown with weeds, or used for dumping waste.

- Weakened community organization as collective maintenance of the structures gradually disappeared.

At the same time, the techniques introduced by the British were poorly suited to the realities of smallholder farming in Bihar. They prioritized large-scale crops and centralized control, undermining localized systems that had supported farmers for centuries.

Today, climate change has brought new challenges such as erratic rainfall, longer dry spells, and more severe floods. These shifting patterns are pushing communities to rediscover the value of ancient farming practices like Ahar-Pynes. With support from local organizations such as our partner PRAN, farmers are beginning to revive these practices, starting with the community of Gungun–Surungabigha.

Schools and villages joining forces to revive the Ahar

PRAN’s early attempts to revive the Gungun–Surungabigha ahar had failed. Farmers and youth tried to scatter seed balls over five years across the site for reforestation. But seeds failed to germinate because of grazing animals and lack of consistent care. Rakesh Prasad, a field officer working with PRAN, said, “We used to do fieldwork near this area in Surungabigha, where I saw this barren ahar. I discussed the idea of tree plantation with the president and villagers. For 5–6 years, we tried planting through seed balls, but it was unsuccessful every time, as animals destroyed them.”

In 2024, PRAN tested a new approach:

- Plant fewer trees with consistent care instead of scattering seed balls.

- Hire a local caretaker, Abdesh, to tend seedlings twice a day.

- Apply natural biofertilizers made locally (SRI Jeevamrit and SRI Bakramrit).

- Engage students from Surungabigha Middle School to expand the green belt.

- Introduce small amounts of diverse seeds such as mango, peepal, sisam, and marigold (genda) to support diversity and soil health.

Over several months, students helped plant neem, gulmohar, and moringa along the ahar. They learned about tree care, water conservation, agroecology, and biodiversity practices, turning the ahar into a living classroom. Their efforts helped expand the plantation area from 1 km to 2.5 km.

Results and ripple effects

The revival hasn’t been easy. Fencing was stolen, bamboo structures broke, and grazing animals damaged young saplings. To overcome these setbacks, PRAN introduced a simple but effective idea: offering a ₹20 (~$0.23) per tree caretaking incentive to engage local youth and farmers in long-term maintenance.

Just one year later, the changes are already visible:

- Land is regenerating: Barren edges are now shaded by young trees, the soil is richer, and biodiversity is slowly returning. The growing tree cover provides shade for neighboring farmers to rest, protects crops, and improves water retention for irrigation.

- Youth are actively engaged in environmental stewardship: Students gain hands-on experience in natural farming, forest management, and soil health. By working alongside farmers, they come to see farming as a dignified livelihood rather than something to avoid, taking an active role in protecting their local villages from droughts and floods. PRAN took the initiative further in another community by developing school kitchen gardens, where students learn practical regenerative farming skills early on.

- Community ownership strengthened: Through shared responsibility, local villages are deeply invested in the ahar’s long-term maintenance.

What was once a neglected water body has become a thriving community space where farmers rest, children learn, and biodiversity returns.

Rethinking the meaning of technology

What springs to mind when you hear “technology?” Satellites, artificial intelligence, rockets, or complex engineering?

Rarely does it relate to something simple.

PRAN’s revival of the ahar system challenges that idea. This ancient network of reservoirs and channels is as ingenious and effective as any modern innovation, perhaps even more so. Its brilliance lies in its principles:

- It unites people instead of concentrating power.

- It regenerates nature instead of exhausting it.

- It serves communities instead of exploiting them.

In the months ahead, we’ll be sharing a series of articles on appropriate technologies for agroecological farmers, celebrating Indigenous knowledge and time-tested practices that can help us face climate change. These are not relics of the past; they are as valuable as any scientific breakthrough, and their lessons extend far beyond the Global South.

PRAN and the Gungun–Surungabigha community are already planning to revive other ahars in nearby villages. Interest is growing, and so is the impact. By supporting this initiative, you’re helping to prove that innovation doesn’t always mean new, expensive, high-tech fixes. Sometimes, it comes from remembering and revitalizing what has already been working for centuries. Indeed, “indigenous knowledge isn’t the past. It’s the future of food.” (Food Tank)

💡 Want more people to know about this initiative? Share, save and like this post on your Instagram!

Invest in traditional farming practices to spread real solutions

Your gift will equip smallholder farming communities across the Global South with the tools, training, and confidence to drive the shift toward regenerative, resilient and fair food systems, where their voices and traditional knowledge lead the way.

Authors: Barsha Koirala and Maylis Moubarak