The Silence of the Land: A Story Written by Young Storytellers from Mexico

"But the years pass, life changes, and the climate changes too. The rains grow scarcer each year, and life becomes harder every day. We worry about the future, the future our grandchildren will live."

As part of an activity within the Youth Storytellers Program with Centéotl in Mexico, youth set out to create a short journalistic chronicle rooted in their own territory. The exercise was designed as a hands-on experience to strengthen writing and research skills, while also putting into practice different tools for observation and contextual analysis.

Throughout the process, the youth worked on preparing interviews, both planned and spontaneous, and on developing skills for engaging with people in their community. The goal was to learn how to listen, ask questions, record information, and recognize the elements that give shape to a local story.

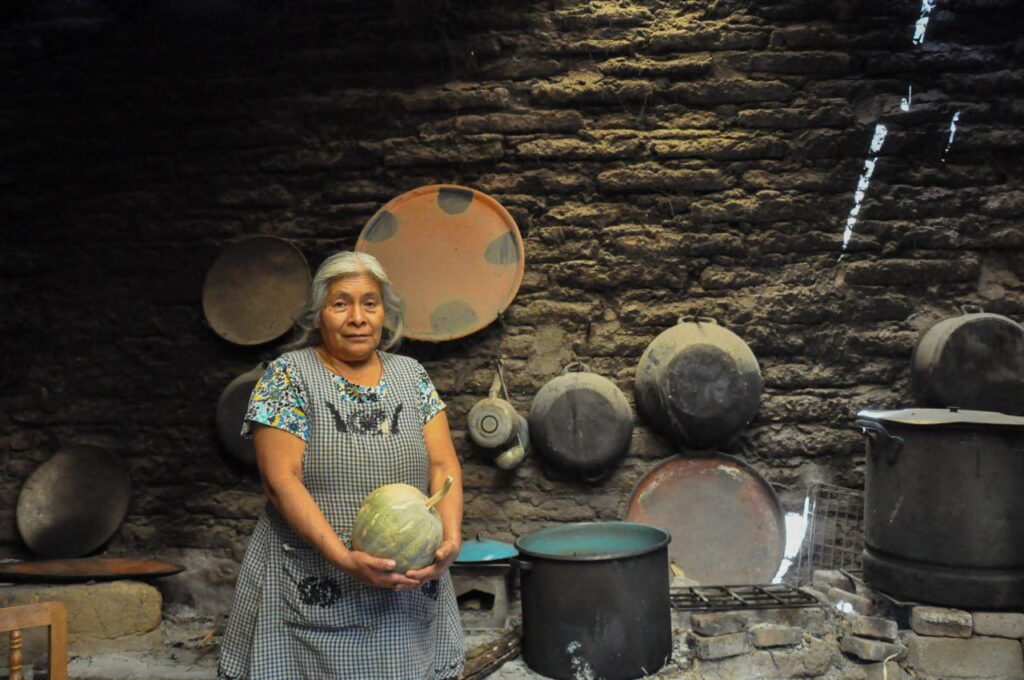

The result of this journey took shape as a powerful written piece accompanied by photographs from rural Oaxaca, told through memory and observation, tracing how climate change, drought, and generational change are reshaping life on the land.

Read the original version in Spanish here

Authors: Rebeca Rubí Martínez Sosa, Felicitas Gutiérrez

Testimonies: Juan Nepomuceno Contreras, Emilia Sosa

Support: Wilber Cuevas

THE SILENCE OF THE LAND

Five in the morning. I open my eyes, and in the distance I hear the roosters crowing. My body already knows the routine, the routine I have carried with me since I was six years old. For those who don’t know me, I am Juan Nepomuceno Contreras Lazo, and this is my wife, Emilia Sosa. We are both from Teotitlán del Valle, and our eyes have witnessed a change we believed would take many more years to arrive. With sadness, I can say that today we are already living it.

Perhaps you still do not understand my worry and sadness, he continues, but it all begins with that routine my father taught me. Every day at five in the morning, my father would wake me up so we could go to the foot of El Picacho mountain, a hill well known in the community for its large fields of alfalfa, milpa, beans, and squash.

As Don Juan spoke, his gaze revealed the pleasure of remembering those green fields full of life, with entire families working the land.

We were no exception. We always went to our fields accompanied by our oxen team and our sheep. As I walked beside my father, I could feel the morning dew falling on my head, the cool air touching my cheeks, and the distinct smell of the earth that I will always remember.

I also remember how, at that same hour, my mother would leave the house carrying her tenate (woven handbasket) of nixtamal, her path always heading toward the village mills. It was a place where buckets of corn from the entire community passed through, ready to be turned into masa for hot tortillas cooked on the comal.

Sixty-eight years ago, everything was different. All families could enjoy a plate of beans with hot tortillas made from our own corn, corn that had been planted and harvested by the same family.

With every word he speaks, the past comes alive, and the fields once again seem vivid and full of color when he says, “I remember that it used to rain very well. My father even planted twice a year. First we planted in February, and later in June. At that time, my father had a pair of oxen that we used to plant alfalfa. Back then, the rains began in February, and the water was so abundant that it collected in the river intakes, and we happily irrigated our crops. In June, the fields grew only with rainwater. In those days, my family used to plant white, purple, and yellow corn, along with beans and squash. Now there has been a very abrupt change that worries me. Young people prepare for the future, but they are forgetting what is most important: the land. That land so valuable, where all our food comes from.”

Don Juan’s story carries weight. It is the voice of a child who once saw rain fall where today only a few drops appear. Standing silently beside him is Doña Emilia, a woman whose life is marked by the same mountain, El Picacho.

“I am Emilia, Juan’s wife, but I am also that girl who was left without a father. When I was very young, my mother taught us how to work the land, and I can still remember those moments at the foot of the mountain. During harvest time, it was an immense joy to see the donkey loaded with ears of corn and squash, all thanks to the rains that never failed.

But the years pass, life changes, and the climate changes too. The rains grow scarcer each year, and life becomes harder every day. We worry about the future, the future our grandchildren will live. Every day I walk to my field with the hope of planting a new tree. Maybe I will not live to enjoy its shade, but I hope my grandchildren will be the ones to enjoy the coolness of that shade.”

Her gaze drifts away, as if remembering the times when the milpas shone, the same place where drought arrived without warning.

“Difficult times are coming. Life is changing. My family is affected by climate change, mainly because of the lack of rain, because we no longer harvest corn like before. Last year we still harvested some squash, but this year none.

Now, for the tortillas to be enough, we have to eat factory-made tortillas along with a few made from our own corn. But we have not lost hope. We continue to care for the land, and we keep planting trees with the hope that the rains will return.

Still, it worries me deeply to think that in twenty years there may be no water. Many things will disappear, and the future of my granddaughters fills me with concern.”

In her voice, one can feel both grief and hope. Each word is a seed, some heavy with sadness, others filled with hope.

The story of Don Juan and Doña Emilia is the story of those who have seen the land fall silent and who have lived the consequences of climate change. Today, each word carries more weight than the last, because it is not only sadness but also a warning. Paths that once began separately have now become one, the same struggle, the same love and respect for the land.

In Teotitlán del Valle, climate change and generational transition are like fields falling silent, where there was once laughter and work. It is the corn that no longer lasts, the squash that once filled the corners of the home and did not appear this year. It is also the trees that are planted and watered with the hope that the old times might return, and that someone, someday, might enjoy their shade.

Here, where handicrafts shine for the world, the land is beginning to fall silent.